Rating: Transsupportive, PEN America, November 9, 2023 (PDF archive 1) (PDF archive 2) (HTML archive) (Take Action)

Action Recommendations

- Suggest/Improve an Action on the GenderMenace.net Action Portal!

Content Summary

America’s Censored Classrooms 2023

Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises

Key Findings

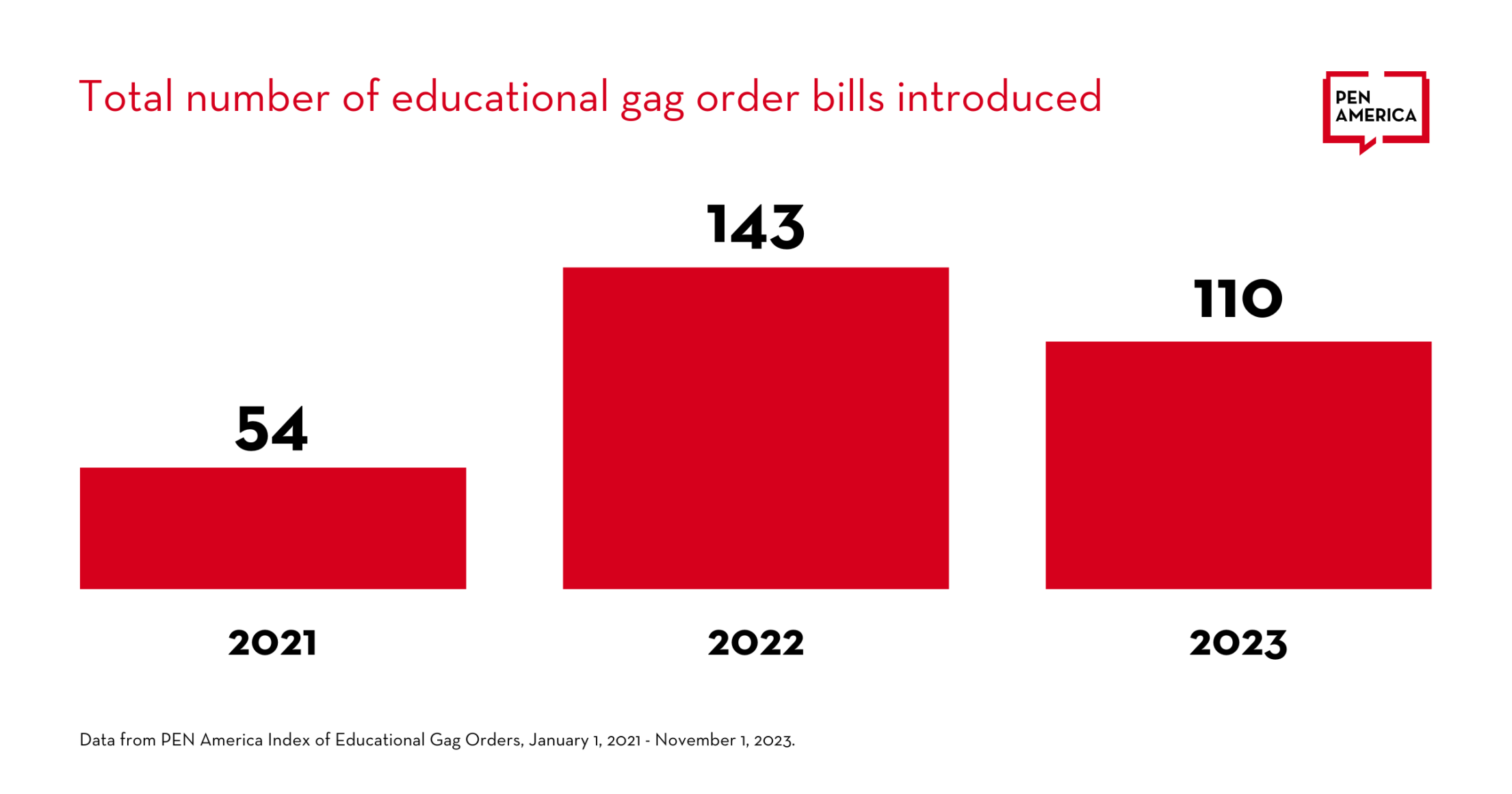

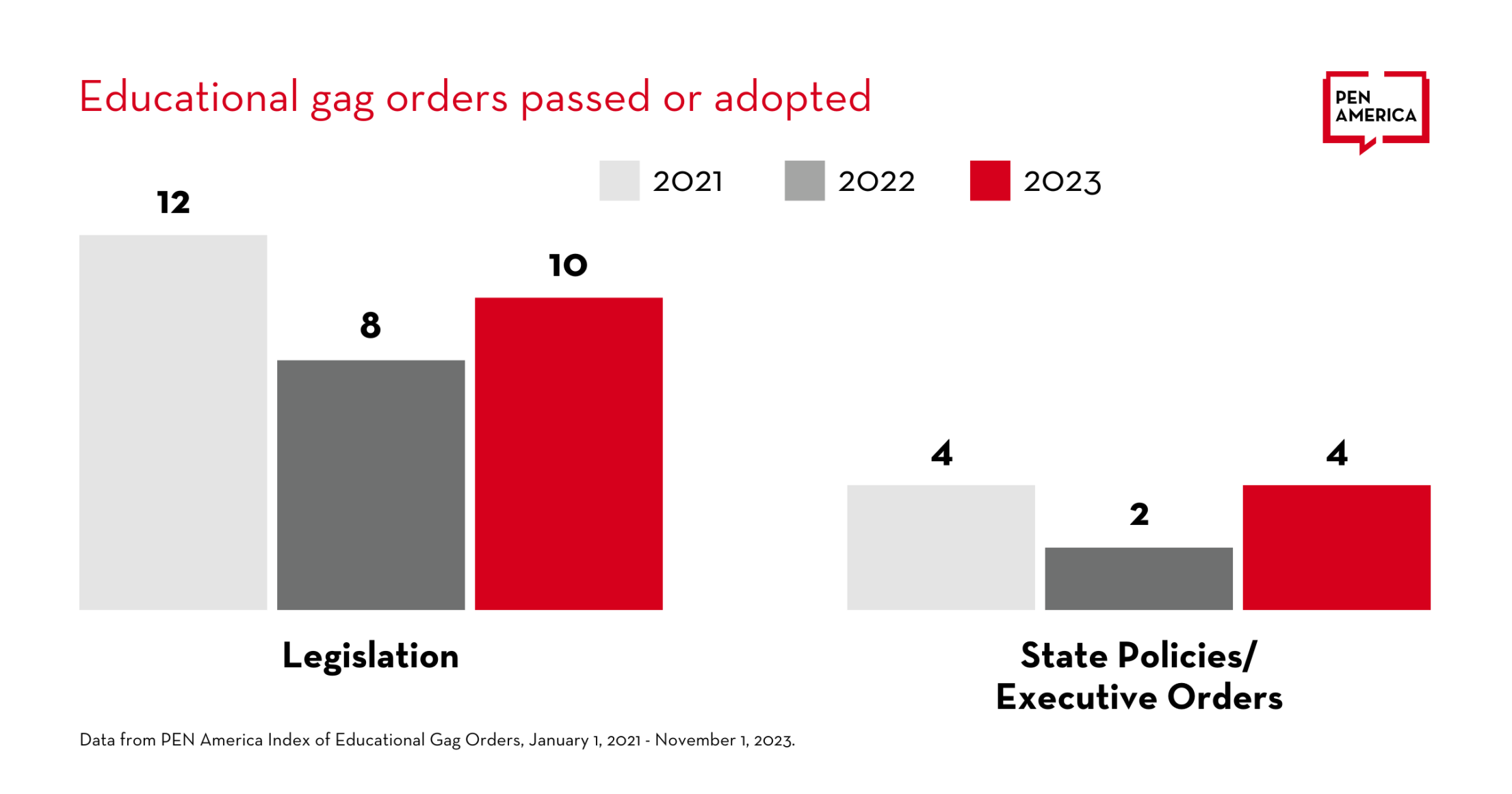

Over the past three years, state legislators have launched an onslaught of educational gag orders—state legislative and policy efforts to restrict teaching about topics such as race, gender, American history, and LGBTQ+ identities in educational settings.1 PEN America tracks these bills in our Index of Educational Gag Orders.

During the 2023 state legislative sessions, 110 bills that PEN America defines as educational gag orders were introduced, and 10 became law. Four more gag orders were imposed via executive order or state or system regulation: two in Florida, and one each in Arkansas and California. These developments bring the number of educational gag orders that have become law or policy to a total of 36 across 21 states as of November 1, 2023.

While it is difficult to guess the total number of educators affected by these laws and policies, a conservative estimate would put the number at approximately 1.3 million public school teachers and 100,000 public college and university faculty.2 The students who have been directly affected—through canceled classes, censored teachers, and decimated school library collections—likely number in the millions. The chilling effect on public education across the country is certainly much larger.

In this report, we analyze the educational gag orders introduced and passed in the 2023 legislative sessions, as well as the impact of laws passed in 2022 and 2021. We find the following trends:

- In 2023, educational gag orders changed dramatically in their shape. Their supporters, who remain overwhelmingly politically conservative, have learned from past mistakes and have new and more insidious strategies for silencing America’s educators.

- Backers of these laws in K–12 schools have shifted their emphasis to bills that restrict speech about LGBTQ+ topics and identities, including numerous copycats of last year’s HB 1557 in Florida, known to critics as the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

- In higher education, legislators have introduced a new set of bills that attack the traditional support network that underpins academic freedom and free speech, including proposed restrictions on university governance, curricula, faculty tenure, DEI offices and initiatives, and accreditation agencies.

- New surveys of K–12 and college teachers affected by educational gag orders show for the first time the extensive toll such laws are having on educators.

- Fortunately, resistance to educational gag orders is rapidly growing. Increasing majorities of Americans have had enough, and organized opposition to educational censorship has increased across the country, with some notable successes.

- In 2024, legislative efforts to censor educational institutions are likely to continue. Each of the past three legislative sessions has seen greater and more varied proposals to impose prohibitions on the freedom to learn and teach in schools, colleges, and universities. The 2024 general election is likely to contribute to ongoing escalation of this trend.

Read an introduction to this report by Eduardo J. Padrón

President Emeritus of Miami Dade College

PEN America Experts

Jeremy C. Young

Program Director, Freedom to Learn

Jonathan Friedman, Ph.D.

Director, Free Expression and Education Programs

Kasey Meehan

Program Director, Freedom to Read

Published November 9, 2023.

Educational Gag Orders, 2021-2023

+

−

Educational Gag Orders, 2023

+

−

Introduction

The game has changed.

It has been nearly three years—and three full legislative cycles—since the first educational gag orders were introduced in state legislatures.3 Throughout 2021 and 2022, most of these bills shared a common set of features that distinguished them from all other kinds of legislation affecting education. First, they were overwhelmingly focused on censoring teaching and classroom materials, in particular concerning the role of race and racism in American history and contemporary life. These were the “critical race theory” bans that took aim at so-called “divisive concepts” in K–12 schools and, at times, in colleges and universities. Second, the overwhelming majority of the bills targeting higher education sought to restrict faculty speech directly. Their objective was both blunt and straightforward: to silence professors.

For three legislative cycles, none of these bills have been especially popular with the general public. At the higher education level in particular, they faced stiff resistance and proved difficult to enforce. Nevertheless, throughout 2021 and 2022, this was the shape most educational gag orders took.

No longer. Since the start of 2023, PEN America has observed a new legislative trend in the country’s statehouses. Supporters of educational gag orders have begun to move on from past legislative approaches that have proven ineffective, in favor of new strategies to silence America’s educators. In doing so, their approaches to K–12 and higher education restrictions have diverged; for the first time, not a single bill that became law in 2023 restricted K–12 schools and colleges at the same time.

For K–12 schools, this has constituted a pivot, synchronized across the country, away from proposing restrictions on speech about race and racism, and toward restrictions on speech about sexual orientation and gender identity. Race is still an object of concern in a number of bills, but the emphasis is now clearly on LGBTQ+ identities. It appears that America’s would-be censors now see proposals to restrict conversations about sexual orientation and gender identity as more of a winning political issue than efforts to restrict discussions of race and racism. Leveraging that presumed support, they have attempted to enact sweeping restrictions on what school-age children can read and learn.

Another pivot involves legislation focused on the country’s public colleges and universities. Early attempts to censor faculty faced stiff opposition not only from the courts but from the many academic groups and processes that underpin academic freedom in the country’s universities: faculty unions, governing boards, shared governance processes, higher education accreditors, and other structures that, collectively, constitute a kind of support network for academic freedom. In 2023, legislators began targeting this academic support system directly. This new breed of legislation is designed to kick the legs out from underneath university governance and autonomy, so that the next time the state moves to censor faculty, no one is in position to push back.

These two changes represent a substantial shift in the who, what, and how of educational gag orders. Only the why remains the same: to silence ideas and identities that some find uncomfortable; control narratives about the past; and ensure that only one set of values, viewpoints, and ideologies makes it past the schoolhouse gate.

At the same time, 2023 has also been a year of mounting resistance to educational censorship laws. Across the country, teachers, professors, students, parents, and community members have pushed back. Some bills that were close to passage were abruptly dropped or watered down in the face of public outrage. Some that became law are being challenged in court. Faculty unions and teachers’ groups are partnering with parents to defend students’ right to learn. As seven former Florida public college presidents wrote in October 2023, for many Americans, “enough is enough.”4

This report consists of five sections. Sections I and II focus on the major trends in educational gag orders and educational censorship legislation that PEN America has observed in the 2023 state legislative sessions.

Section I focuses on those educational gag orders that targeted K–12 schools—gag orders that increasingly are geared toward attacking LGBTQ+ topics and identities.

Section II examines the strategic shift in legislation targeting higher education, where would-be censors have poured their energy into attacking university autonomy, governance, and other institutions or practices that protect academic freedom.

Section III draws on several innovative studies, brought together for the first time, to analyze the impact that three years’ worth of these laws have had on America’s educational system.

Section IV examines the mounting resistance to educational gag orders on both the legal and political fronts.

Race is still an object of concern in a number of bills, but the emphasis is now clearly on LGBTQ+ identities.

Finally, Section V carries the analysis into the 2024 legislative sessions, drawing on emerging trends to identify what are likely to become the next big stories in educational censorship, including

- a continued increase in the number of bills targeting LGBTQ+ content in public K–12 schools;

- an ongoing but diminished focus on restricting how race and racism may be discussed in public K–12 schools;

- more bills to eliminate or undermine the traditional autonomy of public colleges and universities, through proposals to restrict shared governance, faculty tenure, general education curricula, university mission statements, and accreditation bodies; and

- the potential impact of federal court cases and the 2024 general election on educational policy.

The report concludes with an Appendix summarizing all educational gag orders and related censorship bills of concern passed in 2023.

I. K–12: From CRT to “Don’t Say Gay”

In 2021 and 2022, PEN America tracked an initial set of educational gag orders that overwhelmingly targeted speech around race, racism, and American history. President Trump, in remarks delivered in September 2020, set the tone for such an assault, alleging that “critical race theory, the 1619 Project, and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together. It will destroy our country.”5 In response to this perceived crisis, Trump ordered the creation of the 1776 Commission, a White House task force charged with promoting “patriotic education” in the country’s schools. “Our youth,” Trump declared, “will be taught to love America with all of their heart and all of their soul.”6

State lawmakers were listening. In January 2021, the nation’s very first state-level educational gag order was introduced: Mississippi’s SB 2538.7 Declaring that “an activist movement is now gaining momentum to deny or obfuscate this history by claiming that America was not founded on the ideals of the Declaration but rather on slavery and oppression,” the bill proposed to strip state funding from any school where the New York Times’ 1619 Project was taught.8 This was an idea first proffered in 2020 at the federal level, in a bill Tom Cotton introduced in the Senate, that was copied across bills in multiple statehouses in 2021.

Twenty-three proposed gag orders targeting the 1619 Project would follow over the next two years. Dozens more proposals targeted the 1619 Project indirectly, usually by banning discussion of its core ideas. For instance, South Carolina’s H 4392, introduced in 2022, would have forbidden educators from making use of any instructional material that could lead students to believe that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”9 Two such measures were enacted in 2021: Texas’s SB 3 and a Florida Board of Education policy, which both targeted the 1619 Project by name.10

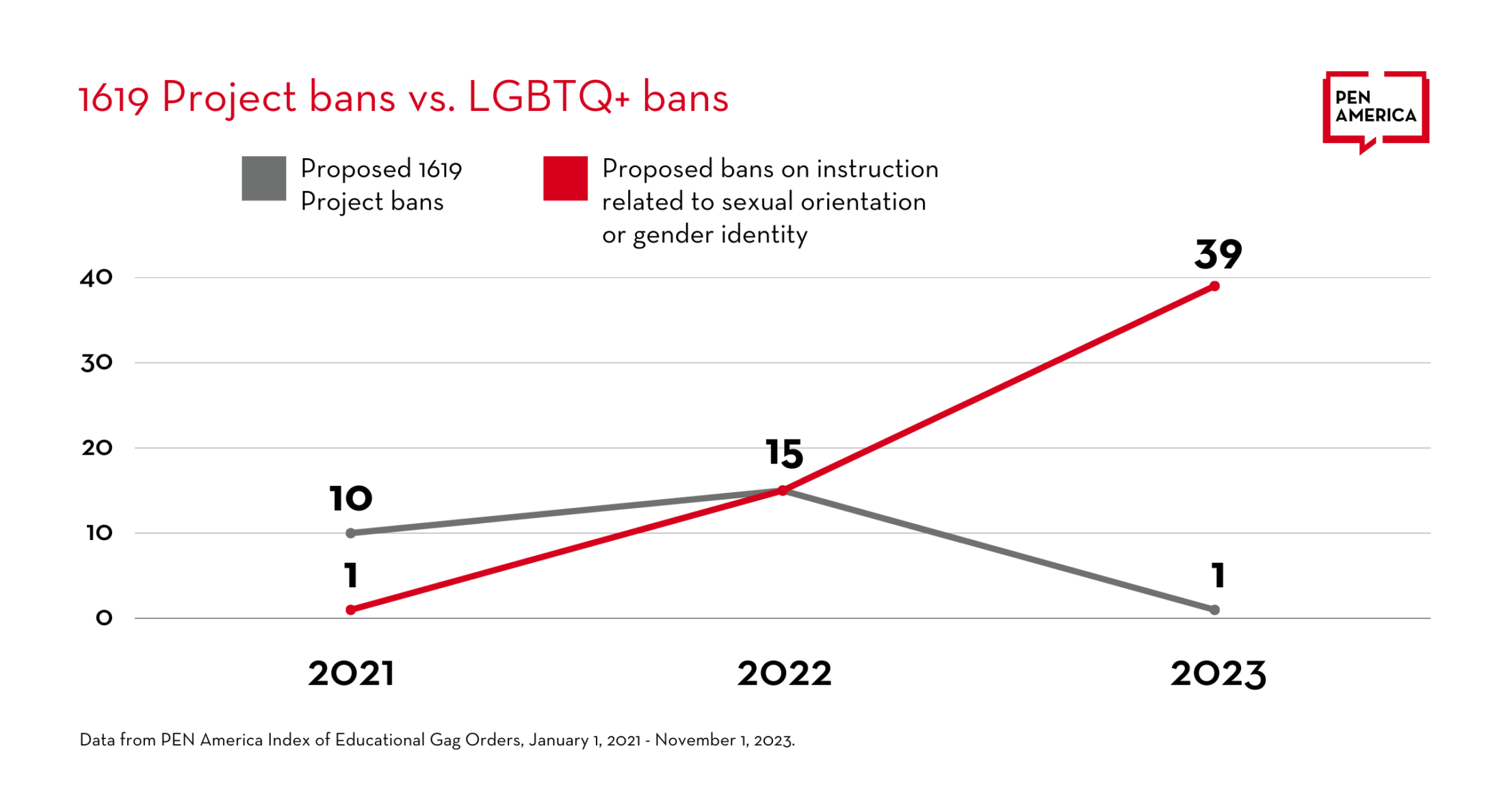

Following two years of efforts to ban so-called “critical race theory” and “divisive concepts,” however, 2023 saw a decline in proposed bills targeting speech in K–12 schools about race and racism. These topics were still discussed and still subject to bans, but with nothing like the intensity of the previous years. About half of bills introduced in 2023 still included some version of the “divisive concepts” list, but that percentage was down significantly from previous years, and very few such bills were passed or seriously considered. In 2023, only a single bill, Missouri’s SB 42, was filed that explicitly targeted the 1619 Project.11

Why the change? There are a few potential explanations. One is that much of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked; most Republican-controlled states have already enacted educational gag orders that target classroom discussions of race. Another is that lawmakers have largely shifted their focus to curricular and governance restrictions—such as bans on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives at universities—rather than classroom instruction gag orders, in part as a response to successful legal action in two cases in Florida, discussed later in this report.

Perhaps the most important potential explanation, however, is that these race-focused gag orders are overwhelmingly unpopular. According to a 2022 national survey from APM Research Lab / Pennsylvania State University, only 13 percent of the public believes that state lawmakers should have a “great deal of influence” over whether or how racism and slavery are discussed in the classroom.12 A survey conducted by the University of Southern California found that large majorities of Americans, including 73 percent of Republicans, want high schoolers to be taught about racial inequality.13 An even more lopsided majority oppose banning books because they discuss race or depict slavery.14 These national findings echo the results of similar polls conducted in Virginia, Florida, and Texas.15

Moreover, those of the general public—parents in particular—are largely supportive of how public schools handle these topics. In fact, according to a 2022 NPR/Ipsos poll, just 19 percent of parents say that the way their local school discusses race and racism is inconsistent with their values, and just 16 percent say the same about how it handles the impact of slavery.16 Even the “war on woke”—arguably the most provocative rhetoric from today’s culture wars—is not polling well, with only 24 percent of Republican voters prioritizing it over law-and-order issues, and many GOP presidential candidates dropping the term from their campaign lexicons.17

Polls are not a monolith on this issue; an American Federation of Teachers poll from Hart Research showed that particular culture-war framings of some race-centered issues could achieve polling majorities (though even this poll was unable to find a popular framing for book bans).18 Such framings rarely exist unchallenged in public discourse, however, and it is difficult to escape the conclusion that race-centered educational gag orders are a political dead end. Steve Bannon’s confident prediction in 2021 that critical race theory bans were “how we win”—and would generate 50 Republican House seats in the midterm elections—seems a thing of the past, at least for now.19

But backers of educational censorship have by no means given up. They have simply shifted focus. In 2023, there was an explosion of gag orders restricting how K–12 educators discuss sexual orientation and gender identity, driven by the same broad group of legislators and advocates previously targeting so-called CRT.

Thirty-nine such bills were proposed this year—more than a third of all K–12 educational gag orders introduced in 2023. All of these bills targeted public schools, and five targeted private ones as well. Most are modeled after Florida’s HB 1557, the 2022 law better known to critics as the “Don’t Say Gay” act. This law states in relevant part that “classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”20

As PEN America noted at the time of its debate in the Florida legislature, this law has a clear discriminatory intent.21 It is not meant to limit instruction related to heterosexuality or cis-identifying people. Rather, it is directed solely at teaching about LGBTQ+ topics and themes, which supporters of the law incorrectly claimed is a prelude to child abuse.22

The law’s discriminatory intent is reflected in subsequent events. Since its passage in 2022, Florida school districts have cited it in banning hundreds of books with LGBTQ+ characters or themes.23Similarly, districts have cited the law in eliminating or sharply curtailing vital resources for LGBTQ+ students, like anti-bullying workshops, trainings, and Pride Weeks.24

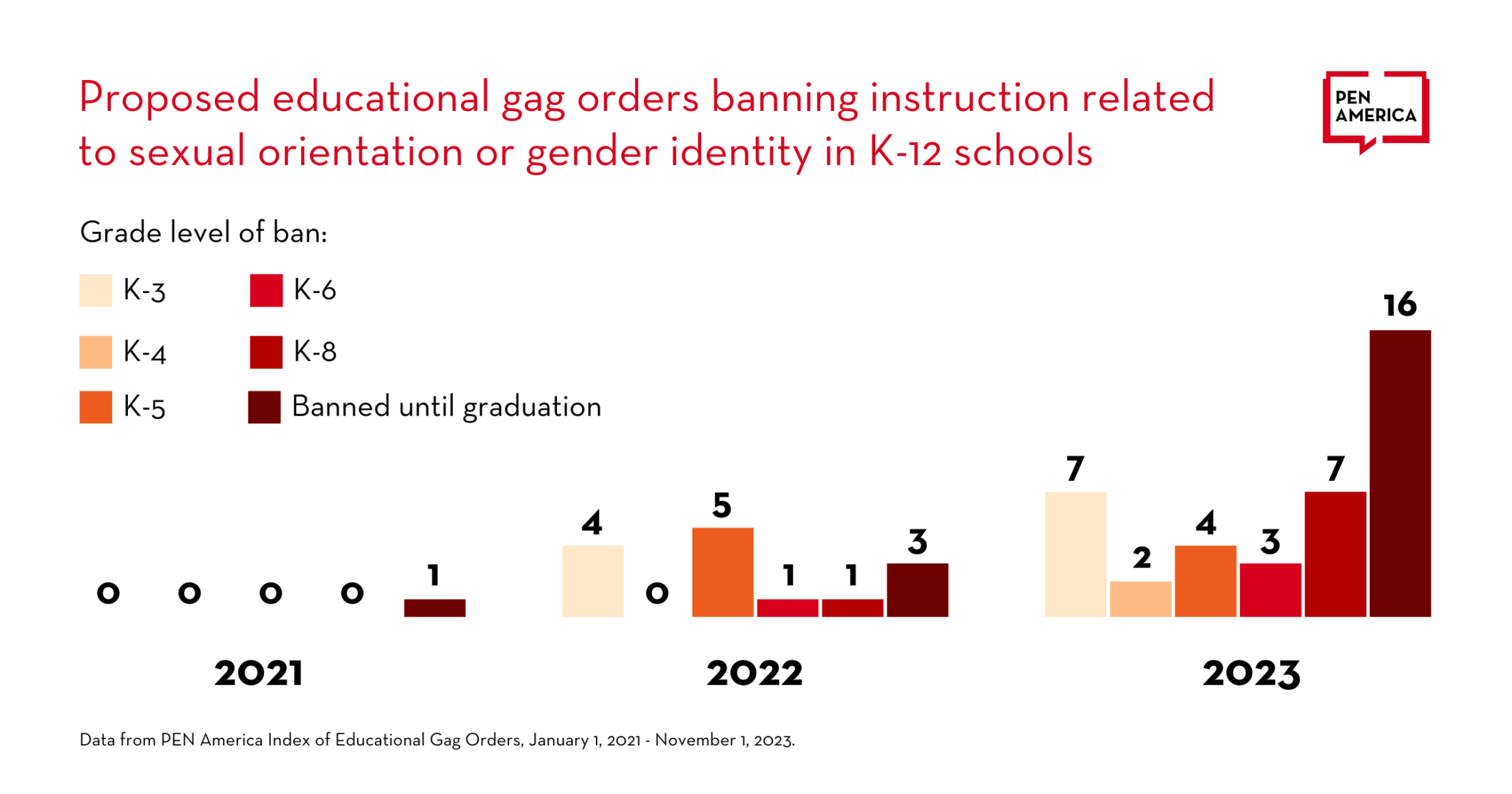

Overall, about three quarters of the 38 educational gag orders targeting LGBTQ+ topics in K–12 schools in 2023 are modeled after HB 1557. Some, such as Wyoming’s SF 117, Utah’s HB 550, and Hawaii’s HB 509, even copy the exact language quoted above.25 But many lawmakers in other states have complained that Florida’s law, which permits limited instruction on these topics after grade 3, is too permissive. “Mine goes further,” boasted Pennsylvania representative Stephanie Borowicz, author of a bill that would have extended the ban until students reach grade 6. In fact, she said, “it really needs to be protected all the way up to 12th grade.”26

And this seems to be the general trend. Over the course of this past year, four bills or policies were proposed that would have extended the ban on LGBTQ+ topics up through grade 5, three up through grade 6, and seven up through grade 8. Sixteen would have banned instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity altogether, blocking discussion of these issues for all grade levels up to and including grade 12.

In Florida, new legislation passed this year (HB 1069) extended HB 1557’s prohibition to grade 8.27Around the same time, a new Florida Department of Education policy introduced a new restriction on these topics through grade 12, stating that instruction related to sexual orientation and gender identity remains permitted after grade 8, but only if “such instruction is required by state academic standards” or “is part of a reproductive health course or health lesson for which a student’s parent has the option to have his or her student not attend.”28 Since Florida’s academic standards do not currently require instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity at any grade level, this regulation amounts to a de facto ban.

Five other such bills became law in 2023 in other states: Kentucky’s SB 150 (a K–12 ban), Iowa’s SF 496 (K–6), North Carolina’s SB 49 (K–5), Arkansas’s SB 294 (K–4), and Indiana’s HB 1608 (K–3). All were in effect as of September 1, 2023.29

Pushing the Limits of Public Opinion

Some of the lawmakers pushing these bills may believe they have the public on their side. There is some evidence to support this idea. The same University of Southern California survey that reported bipartisan support for teaching about racial inequality paints a very different picture when it comes to sex and gender issues. Whereas more than 80 percent of Democrats believe that high school students should learn about gay rights, sexual orientation, gender identity, and trans rights, fewer than 40 percent of Republicans agree.30 For elementary school students, Americans are even less supportive—only about 30 percent overall say they approve of such instruction. There is some variation across demographic groups, with nonwhite and Democratic voters somewhat more likely to support teachers who teach or assign books about LGBTQ+ topics in elementary grades, but the numbers are still quite low.31

When it comes to specific educational gag orders, support appears more tenuous. A bare majority of Americans—51 percent, according to a Morning Consult poll—approve of the core provision of Florida HB 1557 that bans instruction related to sexual orientation and gender identity up to grade 3.32 But support falls off sharply for bans in higher grades, as a YouGov survey shows.33 Even in Florida itself, support for the law may be slipping. A survey by Spectrum News / Siena College found that more Floridians oppose the law (50 percent) than support it (44 percent).34 Parents in Florida appear to be more supportive than voters in the state overall, but two-thirds of Democrats and more than half of Independents are still opposed to HB 1557. Those numbers climb even higher when parents are asked whether the ban should apply up to grade 8. Only Republican parents remain firmly in favor of that expanded scope.35

What is truly being discussed in these surveys can be a little ambiguous, in part because the laws themselves are so vague. It has been unclear if the law in Florida applies to classroom instruction, books in school libraries, and/or books in classroom libraries. Does it apply to field trips? Theatrical productions with LGBTQ+ characters? Teaching about an LGBTQ+ artist and answering a student’s question about their identity honestly? Because topics related to sex and gender can arise in numerous ways in schools, there may not be consensus about what exactly is being deliberated and regulated.

Students in Miami Beach, Florida protest the state’s anti-LGBTQ educational legislation in 2022. (Pedro Portal/Miami Herald via AP)

Nonetheless, these numbers suggest that while there is a potential path to electoral success for gag orders focused on LGBTQ+ topics, that path is a narrow one. But that hasn’t stopped both Florida and national policymakers from competing to see who can adopt the most extreme pro-censorship position. “There was all this talk about the Florida bill—the ‘don’t say gay bill,’” said GOP presidential candidate Nikki Haley during a New Hampshire town hall. “Basically what [HB 1557] said was you shouldn’t be able to talk about gender before third grade. I’m sorry. I don’t think that goes far enough.”36 This sort of positioning may work well in a Republican primary, but it polls much less favorably with the general public. It is possible that legislators are proposing such extreme versions of these bills as political posturing, rather than as serious proposals—but such a distinction is presumably lost on the teachers and students watching as their education becomes a political football.

Nor are lawmakers confining their efforts to Don’t Say Gay–style legislation. Some bills take other approaches to restricting discussion of LGBTQ+ identities. Texas’s HB 1804, for instance, would have banned public schools from “encourag[ing] lifestyles that deviate from generally accepted standards of society.”37 And in Oklahoma, SB 937 proposed to ban what it termed “non-secular self-asserted sex-based identity narrative” in school, including discussion of “a person’s sexual identity or self-identification as homosexual, lesbian, or transgender.”38

A Diminished but Continuing Focus on Race

While the energy and focus of many educational gag orders have clearly shifted toward LGBTQ+ topics and identities, some legislators still have an interest in censoring discussions of race and racism in K–12 schools. Bills of this type in 2023 included Mississippi’s SB 2168, which would have prohibited public schools from teaching “what is colloquially known as ‘critical race theory.’”39 Rhode Island’s HB 5739 would have prohibited “identity politics” and forbidden any instruction that “center[s] any race, ethnicity, gender, religion or viewpoint.”40 South Carolina’s HB 3304 would have prohibited public K–12 schools from offering any “instruction or instructional materials which create a narrative that the United States was founded for the purpose of oppression, that the American Revolution was fought for the purpose of protecting oppression or that United States history is a story defined by oppression.”41 And Texas’s HB 1804 would have required instructional materials in public K–12 schools to only “present positive aspects of the United States and its heritage.”42 While not all of these bills explicitly reference race or racism, their implications for how teachers discuss those issues is plain.

Despite a diminishing focus on race relative to 2022, a narrow majority of gag order bills introduced in 2023—and an overwhelming majority of those focused on race—still draw from the list of so-called “divisive concepts” first laid down in the Trump administration’s Executive Order 13950, on “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping.”43 These bans on vaguely written concepts, so broad that they cast a chilling effect over virtually any mention of race, gender, or identity in the classroom, will be familiar to observers of these trends since 2021. Such concepts were still targeted in approximately half of all gag orders introduced in 2023, including new K–12 laws in Arkansas and Utah and a new higher education law in North Dakota, so they have not gone away.44 But in past years, nearly all proposed and passed educational gag orders were of this type; that is no longer the case.

While the energy and focus of many educational gag orders have clearly shifted toward LGBTQ+ topics and identities, some legislators still have an interest in censoring discussions of race and racism in K–12 schools.

Bans on Social-Emotional Learning

Finally, a small number of bills this year took aim at social-emotional learning. This ordinarily noncontroversial pedagogical approach has been around in some form since the 1960s, and as an organized pedagogy and research area since at least 1994.45 It emphasizes the importance of teaching students how to understand and manage their emotions, but it has recently been misidentified by conservative conspiracy theorists as a Trojan horse for “critical race theory” and “liberal indoctrination.”46

Under North Dakota’s HB 1526, public K–12 schools would have been forbidden from teaching that a “student’s inner feelings are capable of guiding the student’s life” or “inform[ing] a student’s worldview based on emotions.”47 And Oklahoma’s SB 1027 would have prohibited schools from using any instructional materials that address “non-cognitive social factors including but not limited to self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision making, and/or other attributes, dispositions, social skills, attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, feelings, emotions, mindsets, metacognitive learning skills, motivation, grit, self-regulation, tenacity, perseverance, resilience, and/or intrapersonal resources.”48

Observers of educational censorship laws will want to follow this trend closely. Such language has made an appearance in statehouses across the country this year and will likely play a role in the 2024 legislative session as well.49

Adaptation and Its Limits

Supporters of gag orders in K–12 schools appear to be shifting toward new bill types they view as more politically advantageous to them, particularly bills focused on sexual orientation and gender identity. But it is unclear whether their new tactic will overcome popular resistance to censorship. Americans may say they support bans on instruction related to sexual orientation and gender identity, but it is unclear whether they would feel similarly if they learned that these bans are, as is so often the case, being used to marginalize LGBTQ+ students or students with LGBTQ+ family members, and to prohibit any representation or mention of such identities in schools. And as noted above, lawmakers continue to introduce legislation that proposes ever-more-radical forms of censorship in K–12 institutions.

II. Higher Education: From Educational Gag Orders to Erosion of Academic Freedom

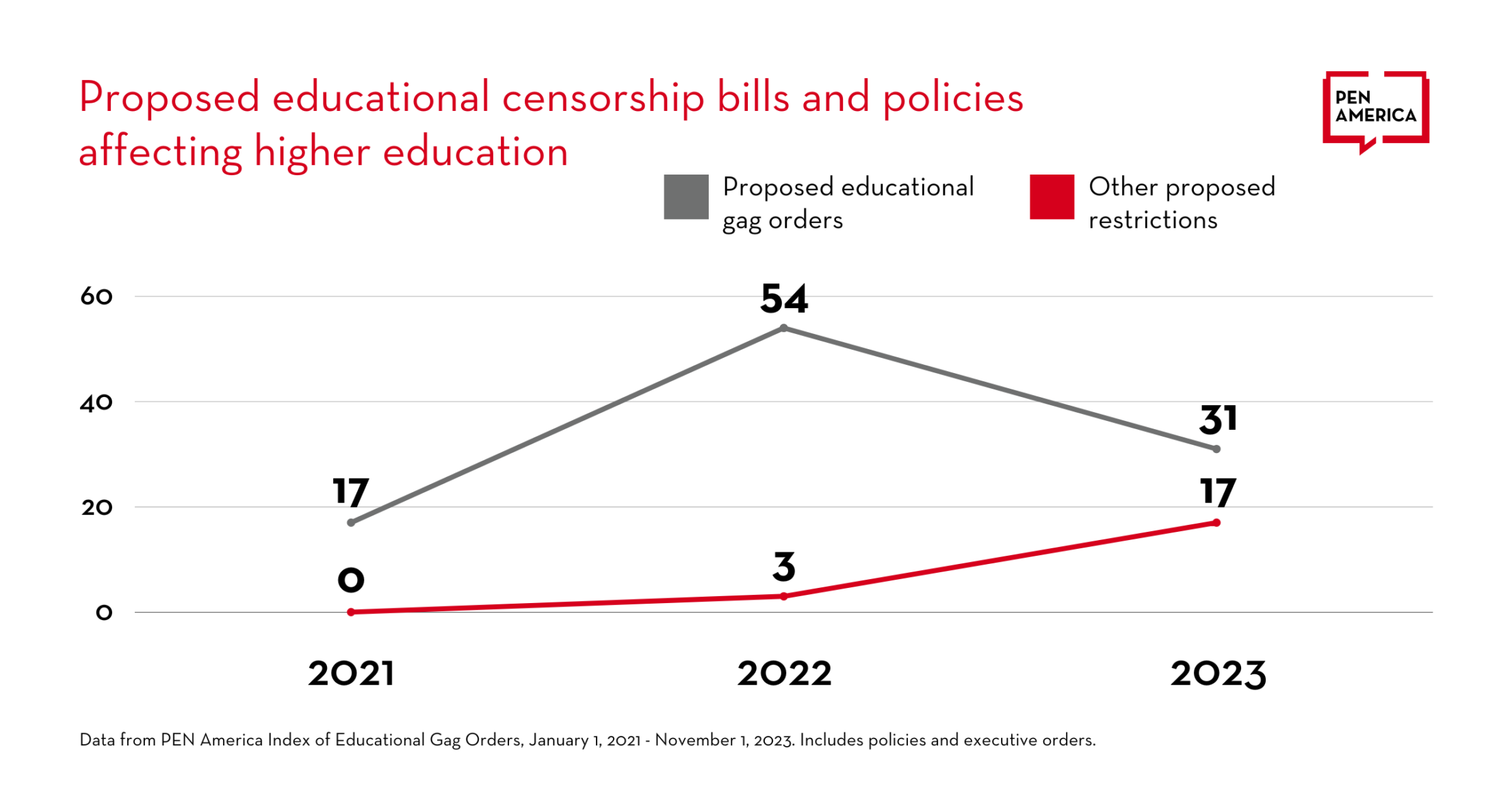

Just as in the K–12 space, legislators largely changed their list of targets for censorship bills geared toward higher education in 2023. In part, the reasons for this change were also the same: to jump from a less-popular target to one perceived as more politically acceptable.

Bills that propose to regulate what college and university faculty can say or teach poll quite poorly. When asked who should have a great or good deal of influence on what is taught in college, 68 percent of Americans say professors. Only 37 percent say it should be the state government. Crucially, there is no partisan split on this issue; Democrats and Republicans are equally opposed.50Nor does the picture change when a specific educational gag order is described. For example, Florida recently passed SB 266, arguably 2023’s most censorious gag order, which, among other things, bans ideas associated with “critical race theory,” as well as campus activities or programs that promote DEI.51 But when Floridians were asked last March whether they would support a bill with these provisions, 61 percent said no. Even among Republicans, just 56 percent were in support, compared to 38 percent opposed.52

At Iowa State University, university counsel have told faculty that their classroom speech may be restricted by HF 802. Photo credit: Tony Webster/Flickr

Importantly, these higher education gag orders are losing not just in the court of public opinion but in actual court as well. When Governor Ron DeSantis began touting the Stop WOKE Act in February 2022, he declared Florida “the state where woke goes to die.”53 But today it is the Stop WOKE Act itself that is on life support. In November 2022, a federal judge declared the parts of the law that censor college and university faculty to be unconstitutional, blocking it from going into effect.54 (A separate lawsuit resulted in a stay of the portions of the law that censor private institutions, including private colleges and universities.)55 Because SB 266 builds on and expands the Stop WOKE Act, significant parts of that law are effectively blocked as well.

And even where higher education gag orders are not blocked, enforcement has been spotty at best. Last year’s America’s Censored Classrooms report described one example. At Iowa State University, university counsel have told faculty that their classroom speech may be restricted by HF 802, a law passed in 2021, especially if their course is a required one.56 Not so at the University of Iowa, where leaders have assured faculty that the law has “zero impact” on instruction and that they should continue to teach as normal.57 This inconsistency is not uncommon in states where educational gag orders are in force, and colleges and universities have issued differing guidance based on varying interpretations.

| A Liberal Educational Gag Order Since 2021, virtually all bills and policies classified by PEN America as educational gag orders have emanated from the political right. In 2023, however, one significant and concerning policy gag order came from the left. In May 2022, the Board of Governors of California’s community college system voted to adopt new regulations around DEI.58 These regulations were then submitted to the Department of Finance for approval, which was granted in April 2023. In addition to normal criteria around teaching, scholarship, and service, faculty must now demonstrate that they employ “DEIA [diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility] and anti-racist principles, and in particular, respect for, and acknowledgement of the diverse backgrounds of students and colleagues to improve equitable student outcomes and course completion.” While not necessarily censorious on its own, this rather vague regulatory language has been supplemented by additional documents that go further, threatening to gag the research and pedagogy of tens of thousands of California community college faculty. In a state guidance meant to aid community colleges in implementing the regulations, faculty are instructed that they may satisfy these new requirements by adopting or affirming a highly specific set of practices and ideologies, including that they “demonstrate an ongoing awareness and recognition of racial, social, and cultural identities with fluency regarding their relevance in creating structures of oppression and marginalization,” “develop and implement a pedagogy and/or curriculum that promotes a race-conscious and intersectional lens,” and “participate in a continuous cycle of self-assessment of one’s growth and commitment to DEI and acknowledgement of any internalized personal biases and racial superiority or inferiority.”59These instructions are framed as being recommendations only, but a separate letter from the Chancellor’s Office makes clear that these are to be considered a “baseline” that faculty “must demonstrate” in order to be employed, promoted, or tenured in the community college system.60 It is easy to see how this language threatens the academic freedom and free speech of faculty. To be considered for tenure, must a biology professor now seek out ways to promote “a race-conscious and intersectional lens” in the classroom? How and to whom must faculty now demonstrate that they recognize their own “biases” and feelings of “racial superiority or inferiority”? Are faculty now required to affirm, as a condition of their employment, that they and every other societal structure are racist? If this is the “baseline” for faculty to demonstrate, what room is there for them to teach a range of theoretical frameworks or interpretations? What space is there for disagreement or even debate over what is in effect a highly prescriptive and ideological directive about these matters?Experience in other states suggests that these are far from baseless hypotheticals. Indeed, we have seen similarly vague language chill academic speech in similar ways following the passage of educational gag orders in Florida, Iowa, and Oklahoma.To be clear, these regulations go far beyond the DEI policies found in the vast majority of public colleges and universities in the country. For example, faculty at the University of California who are going up for tenure are also evaluated for their contributions to DEI.61However, the standards under which they are evaluated are much less ideologically prescriptive and, crucially, may be used or not used by tenure review boards as they see fit. By contrast, the criteria for California community college faculty under this policy are highly ideological and specific and presented as a “minimum standard.” As such, they represent a major threat to the academic freedom and free speech of faculty—one of the most censorious educational gag orders we have seen, and the only one to become law or policy in a state where Democrats control all branches of state government. |

In the face of these setbacks, some conservative supporters of educational gag orders have seemed inclined to persevere. This year, 29 new educational gag order bills, as well as two executive orders or regulations, were proposed that target higher education. This amounts to 25 percent of all gag order bills introduced in 2023. Nevertheless, this constitutes a drop from 2022, when 54 higher education gag orders were proposed.

But educational gag order supporters have not given up on higher ed, even if they have largely pivoted from targeting faculty members’ expressive freedoms directly. Instead, they are now going after the assemblage of people, institutions, and practices that defend them.

The Support Structure for Academic Freedom

Academic freedom and campus free speech have many defenders. Courts have long recognized academic freedom as a special concern of the First Amendment.62 Tenure protections, enshrined in collective agreements and defended by faculty unions, ensure that faculty cannot be disciplined or dismissed for political reasons. Accreditation bodies can downgrade or decertify institutions that repeatedly violate academic freedom, costing these institutions millions of dollars in federal funds. Principles of shared governance, such as the 1966 American Association of University Professors (AAUP) Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities, ensure that “the faculty has primary responsibility for such fundamental areas as curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction, research, faculty status, and those aspects of student life which relate to the educational process.”63

And long-standing norms around institutional autonomy insulate public higher education institutions from undue political interference, enabling them to craft their own mission statements and make their own programmatic decisions, and preserving them as spaces where ideas both popular and unpopular can be discussed, studied, and learned from. As the American Association of Colleges and Universities and PEN America wrote in a joint statement in June 2022, “In the United States, the content of what is taught and discussed in higher education classrooms is shielded from direct governmental control. Colleges and universities are self-governed and self-regulated. . . . Legislative restrictions on freedom of inquiry and expression violate the institutional autonomy on which the quality and integrity of our system of higher education depends.”64

Together, these defenses function as a kind of academic immune system, shielding individual faculty from censorship. It is this system on which educational gag order supporters are now training their fire.

In 2023, these proposals to restrict the autonomy and governance of higher education institutions took four main forms: curricular control bills, tenure restrictions, DEI bans, and accreditation restrictions.

Curricular Control Bills

Curricular control bills are pieces of legislation designed to assert state control over curricula in public colleges and universities. This includes both general education curricula and the approval or retention of academic programs.

Rather than censor individual faculty speech in the classroom, curricular control bills allow lawmakers and political appointees to dictate academic programming. For example, they might order the shuttering of departments or academic institutes, cancel courses, or eliminate majors. At least on paper, individual faculty members are still free to teach and carry out research as before—they just may no longer have a program, classroom, or laboratory in which to do it.

Why have curricular control bills become so popular? It appears that some conservatives gravitated toward this tactic in the wake of the federal court’s injunction against the Stop WOKE Act, believing that curricular control had a better chance of surviving constitutional scrutiny than educational gag orders. This new strategy of curricular control was ably described by Adam Kissel, a visiting fellow in the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy. In a December 2022 piece for the Federalist, Kissel offered what he called “the smart lawmaker’s guide” to writing educational censorship lawsthat will stand up in court.

A public college cannot and should not control the viewpoints expressed in the classroom. Instead, a public college or a state legislature should assert its prerogative over the content of the curriculum at various levels.

Consider the subject of astrology. It would be reasonable for a department of astronomy, its university, or its state legislature to make a determination that astrology readings are an unserious waste of time. . . .The same is true for other subjects, including CRT. A college department, a university, or a legislature may, as a matter of content and careful judgment, either require or prohibit modules, units, and courses on any topic. Further, the university or the legislature might determine that an entire program or department is not sufficiently valuable to receive scarce resources. . . .

Determining institutional priorities is a core responsibility of institutions of higher education. When public colleges fail to do that work effectively, it is appropriate for legislatures to fill the gap.65

In 2023, Christopher F. Rufo, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a leading educational gag order activist, made a similar claim, arguing that academic freedom attaches only to the individual faculty member, not to the college or university as a whole, and certainly not to its constitutive departments or units. Rufo wrote,

It is not a violation of “academic freedom” to close down ideologically captured or poor-performing academic departments; it is, to the contrary, part of the normal course of business. Legislators in states such as Florida and Texas, which will both be considering higher education reform this year, should propose the abolition of academic departments that have abandoned their missions in pursuit of shoddy scholarship and ideological activism.66

As a trustee of New College of Florida, a small public liberal arts institution, Rufo has had the opportunity to put his plan into action. In August 2023, he and a majority of his fellow trustees voted to begin the process of abolishing the university’s gender studies program, a step he says was necessary because the program contradicted his conception of “the true, the good, and the beautiful.” This approach is an alarming departure from the normal process of approving and closing departments, which typically originates with university administrators and faculty and focuses on enrollment, mission, and financial concerns.67

Ideologically motivated curricular control of this nature is not new. The conservative majority on the University of North Carolina’s Board of Governors, for instance, has a long history of closing institutes and eliminating programs for ideological reasons.68 What is new, however, is the growing movement among politicians to influence or even mandate curriculum in higher education via legislation.

The most notable example is Florida’s SB 266, which became law in May 2023. Among other things, this law prohibits public colleges and universities from using public funds to promote or support any “programs or campus activities” that violate the Stop WOKE Act or that “advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion, or promote or engage in political or social activism.” Importantly, this language restricts core faculty instruction and research just as easily as it restricts DEI offices, as draft regulations prepared in October 2023 by the University of Florida Board of Governors make clear.69SB 266 also directs universities to review their programs “for any curriculum that violates [the Stop WOKE Act] or that is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities,” and it bans general education courses that “distort significant historical events” or teach “identity politics.”70

SB 266 is a deeply censorious law, but note that except for expanding the scope of the Stop WOKE Act, it has very little to say about faculty speech directly. Instead, it targets the programs and institutes in which Florida faculty do their work, and the ability of courses featuring certain ideas to be counted toward general education requirements. This is an important distinction, albeit one that is still extremely likely to result in rampant self-censorship—and institutional censorship as well; in October 2022, Florida A&M University recently cited SB 266 when the university defunded a student group’s participation in a local Pride Parade.71

Similar proposals have been floated in other states. Earlier this legislative session, lawmakers in Wyoming considered but ultimately rejected a budget amendment to prohibit the University of Wyoming from using state or federal funds for “any gender studies courses, academic programs, co-curricular programs or extracurricular programs”—a measure they also considered last year.72 (The initial draft of the legislation that became Florida’s SB 266 proposed to do likewise.)73

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signs legislation on Monday, May 15, 2023, banning state funding for diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at Florida’s public universities, at New College of Florida in Sarasota, Fla. (Douglas R. Clifford/Tampa Bay Times via AP)

Other bills are less explicit but are likely preludes to something similar. Tennessee’s HB 1115 would have transferred the authority to terminate academic programs from public universities’ boards of governors to the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, distancing it from the universities themselves and bringing it closer to state lawmakers’ control.74 And Ohio’s alarming SB 83, which was passed by the state senate and is still live as of this writing, would require public universities and their constituent units to “ensure the fullest degree of intellectual diversity” on matters like course approval, general education requirements, common reading programs, strategic goals for departments, student learning outcomes, and invited speakers.75 What the law means by “intellectual diversity” or how it can be satisfactorily demonstrated to “the fullest degree” is unclear.

Tenure Restrictions

A second type of bill targets faculty tenure. Tenure is one of the bulwarks of academic freedom—at least for the minority of faculty who hold it, as many faculty hold non-tenure-track or contingent appointments.76 The roots of tenure in fact lie in the belief that scholars require special protections by colleges and universities so that they can engage in academic work without fear of retribution. As the AAUP wrote in its 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, “The common good depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition.”77

So it should be no surprise that would-be censors have made ending tenure one of their central goals.78 This approach was reflected in a number of bills this year, including Iowa’s HF 48; North Carolina’s HB 715; Mississippi’s SB 2785; and the initial version of Texas’s SB 18, which passed the state senate before being amended in the house. All would have eliminated tenure or blocked institutions from awarding it going forward.79

Other bills proposed this year would have formally left tenure intact but significantly weakened the protection it confers. For example, North Dakota HB 1446 proposed to allow two of the state’s public universities to terminate faculty for failing to “[exercise] mature judgment to avoid inadvertently harming the institution, especially in avoiding the use of social media or third-party internet platforms to disparage campus personnel or the institution.”80 Ohio HB 151 would have required tenured faculty to undergo an annual performance evaluation, during which they would be scrutinized according to whether they “create a classroom atmosphere free of political, racial, gender, and religious bias.” Negative evaluations could have resulted in revocation of tenure.81

None of these extremely restrictive provisions became law in 2023, in part because tenure policies draw support from across the political spectrum.82 However, two new laws—the final versions of Florida’s SB 266 and Texas’s SB 18—nudge those states’ policies away from robust tenure practices and give more authority to university presidents in making final determinations about the retention of tenured faculty. SB 266 in particular erodes the power of the state faculty union and ends binding arbitration for faculty employment disputes, meaning that faculty who believe that they were disciplined for engaging in protected speech have lost many of their options for defending themselves.83

DEI Bans

A third type of bill seeks to restrict DEI programs and initiatives on campus. Such bills, where passed, often undermine academic freedom and free expression on campus by asserting direct ideological control over how universities operate. Content- and viewpoint-based censorship of university activities or decision-making creates a broad chilling effect that affects all aspects of university life, including on faculty and student speech. This dimension of Florida’s newly passed SB 266 was already described above, and many other states are moving in the same direction.

Texas SB 17 bans DEI offices from campus and calls into question the legality of student-run groups. Photo Credit: Nick Amoscato/Flickr

Texas’s SB 17, the most significant new law of this type, bans DEI offices from campus and prohibits institutions from “promoting policies or procedures designed or implemented in reference to race, color, or ethnicity.” Such language is so expansive that it calls into question the legality of UT–San Antonio’s Black Student Union, or UT-Austin’s Latinx Community Affairs, a student-run agency that organizes events for the university’s Latinx students and staff. This version of SB 17 became law in June 2023, but an early draft went even further, proposing a statewide blacklist banning faculty and staff who “violated” the law from being employed in any state public institution of higher education for a year, or for five years after a second violation.84

DEI bans like these are becoming increasingly common. Similar efforts were mounted this year in Ohio, Arizona, and Iowa, among other states.85 Ohio’s SB 83 is especially alarming. If passed, it will prohibit “any mandatory programs or training courses regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion”; forbid university administrations to “endorse or oppose” concepts such as “sustainability,” “inclusion,” and “marriage”; and mandate university discipline for any students found to have violated the “intellectual diversity rights” of anyone on campus.86 This is deeply chilling language that, in the name of regulating DEI, inserts the government into every facet of university life to hunt for supposed violations of these very specific prohibitions.

And in Missouri, SB 410 would have taken aim at “DEI ideologies,” defined in the legislation as any topic dealing with “antiracism, implicit bias, health equity, and any other related instructions or that promote differential treatment based on race, gender, religion, ethnicity, and sexual preference.” Though it did not pass into law, had SB 410 been adopted, the bill would have prohibited colleges and universities from requiring students to “answer any questions” related to these topics over the course of their studies.87 The chilling effect of such a law on faculty and student interaction, both within the classroom and without, would have been vast.

This is deeply chilling language that, in the name of regulating DEI, inserts the government into every facet of university life to hunt for supposed violations of these very specific prohibitions.

| Diversity Statements in Higher Education Some DEI restrictions proposed or passed in 2023 focused on prohibitions on the use of diversity statements in the hiring and promotion process for faculty. Many of these bills can be found in the Chronicle of Higher Education’s DEI Legislation Tracker.88When universities require faculty members or job candidates to author diversity statements as part of hiring or promotion, it can raise significant concerns for faculty members’ academic freedom. Such a requirement can convey the message that only certain approaches, language, and ideas about diversity and equity are considered acceptable. This can distort how faculty carry out their professional duties, forcing them to adopt positions in their teaching or research that they do not genuinely support. It can also narrow the prospects for meaningful dialogue and debate on campus around complex social and political issues.On the other hand, there are instances in which personal background, individual experience, and identity are germane to academic and scholarly work. Moreover, academic hiring and promotion committees should care about whether a candidate understands and supports students of diverse backgrounds, affiliations and viewpoints. Statements on such subjects may provide evidence of the ability to deal effectively with students of all identities and persuasions. However, any such statements should be voluntary; when questions are asked on such subjects, a variety of viewpoints and approaches should be accepted in response.Because of this complexity, PEN America disfavors legislative or regulatory efforts to ban the use of diversity statements in the hiring and promotion process at colleges and universities, out of concern that they could preclude consideration of useful information about a candidate’s qualifications. As such bills have a limited and only indirect impact on educational expression, they are included in PEN America’s Index of Educational Gag Orders only if they contain some additional, more explicitly censorious provision. |

Accreditation Restrictions

The fourth and final type of higher education bill that PEN America tracked in 2023 involves legislation targeting college and university accrediting agencies. The rise of these bills is especially alarming, since accrediting agencies historically have served as bulwarks against undue political influence on university governing boards—a type of influence for which educational gag orders, curricular restrictions, and attacks on tenure and DEI certainly qualify.89

Accreditation is one of the principal guarantors of quality in America’s higher education system and one of the major ways students can differentiate between a reputable institution and a diploma mill.90 Each accreditor has its own standards for issues like graduation rates, financial health, and curricula. Accredited institutions themselves help develop these standards, as well as plans for their implementation and evaluation. Ultimately, public and private universities must meet these standards to acquire and maintain accredited status.

And they have a very good reason to do so. Under the federal Higher Education Act, unless a college is accredited by a federally recognized agency, its students are ineligible for Pell Grants, federal loans, and work-study funds; nearly 84 percent of all college students rely on this financial support.91 Without accreditation, graduates may also have difficulty getting their degrees recognized by prospective employers or licensing boards. For the majority of universities, de-accreditation amounts to a death sentence.92

Accreditation is one of the principal guarantors of quality in America’s higher education system and one of the major ways students can differentiate between a reputable institution and a diploma mill.

This is the dynamic that some lawmakers and commentators want to change, and for one specific reason: because accrediting bodies are a shield against government censorship. Accreditation agencies have pushed back against educational gag orders, warning lawmakers that passage could imperil the accreditation of their state’s colleges and universities.93 They have also helped to defeat attacks on faculty tenure, including in North Dakota, where fears over losing accreditation torpedoed this year’s HB 1446. On DEI initiatives, both Florida’s SB 266 and Texas’s SB 17 were scaled back significantly by lawmakers concerned about meeting accreditation standards.94

In short, institutional accreditors are one of higher education’s final lines of defense for academic freedom. But it is unclear for how much longer this will be the case.

In June 2023, Florida sued the federal government in an attempt to sever the link between accreditation and federal aid altogether.95 And even if the suit fails, Florida has already prepared a backup plan: a new law that allows state universities to sue an accreditor for any financial harm it suffers due to a “retaliatory or adverse action” taken by an accreditor. In other words, Florida can sue an accreditor that enforces its own standards. This provision strikes at the very purpose of accreditation. Nonetheless, it has already been copycatted: Texas’s new DEI ban law, SB 17, contains similar language.96

Lawmakers in North Carolina added a similar provision into an otherwise unrelated bill at the last moment this legislative session, and it has now become law too. HB 8 requires public colleges and universities to switch accreditors each review cycle, a time-consuming and costly provision that North Carolina lawmakers copied from SB 7044, a bill passed in Florida last year.97 In both instances, the intent is to weaken the power of accreditation agencies.98

HB 8 will also allow public colleges and universities in North Carolina to sue anyone who intentionally or recklessly makes a false statement to an accreditor that, as a result of any ensuing review, causes the college or university to “incur costs.” These provisions are in direct response to a letter from the University of North Carolina’s accreditor seeking details about how a new academic center championed by conservatives came to be approved.99 Under the new law, anyone raising questions to an accreditor about a university process runs the risk of being sued by the university for doing so—timing that hardly appears entirely coincidental. Accordingly, HB 8 will make future investigations of this type much less likely.

These laws enter a landscape where nonpartisan accreditors are being increasingly politicized by some conservative activists. In June 2023, a Heritage Foundation report called for Congress to “dismantle the higher education accreditation cartel” by creating “an alternate path to Title IV funding eligibility”—that is, by decoupling accreditors’ seal of approval from eligibility for federal student financial aid.100 Florida governor Ron DeSantis has pledged that, if elected president, he will work to remove accreditation from institutions that house DEI initiatives and to authorize “alternative accreditors” in order to “totally blow up the accreditation cartel.”101 Former president Donald Trump has promised to do something similar if he is reelected in 2024.102

Kyle Beltramini of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, a nonprofit organization that has sought to undermine accreditation for decades, wrote in June that “the recent spate of legislation introduced at the state level seeking to challenge the national (formerly regional) accreditors is unprecedented.”103 He is right.

What all of this amounts to is a new stage in the legislative war on academic freedom and free speech. Rather than simply taking away faculty members’ right to speak, many conservative lawmakers are going after the support structure that makes faculty speech possible, imposing direct political and ideological control over university governance. The long-term goal appears to be steadily chipping away at this academic support structure, knocking down one layer of defense after another until educators, as well as the colleges and universities that employ them, are brought fully under this new brand of state-mandated ideological control.

Accreditation agencies have pushed back against educational gag orders, warning lawmakers that passage could imperil the accreditation of their state’s colleges and universities.

III. Impact: The Silencing of Educators

Since January 2021, 30 educational gag orders have become law, and a further 10 have gone into effect via state or system policy or executive order. Twenty-four of these educational gag orders, in 21 states, have impacted K–12 schools. For higher education, the numbers stand at 13 educational gag orders in 11 states. In addition, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas all passed laws in 2023 that attack college and university autonomy.

For much of the last three years, evidence of the impact of these laws on educators has been hard to come by except via individual anecdotes. No longer. Since late 2022, multiple surveys of educators have appeared, allowing us for the first time to take stock of how these laws are affecting K–12 and college teachers.

The most notable of these surveys are two major studies by researchers at the RAND Corporation, which surveyed 8,000 K–12 educators and elicited open-answer comments from over 1,400 of them.104 Other studies of K–12 schools have been compiled by education researchers at UC–San Diego and the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access and from the National Association for Music Education. For higher education, researchers at state conferences of the AAUP conducted a survey of over 4,000 public university faculty in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas.105 Several investigative reports by journalists have documented additional examples of how these laws have impacted educators.106

Examined together here for the first time, these studies paint a comprehensive picture of the vast chilling effect that educational gag orders are having on the tens of thousands of educators—and, by extension, the millions of students—to whom they apply.

Public K-12 Schools

Among public K–12 school educators, the primary response to these educational gag orders has been fear, and with good reason. According to the 2022 RAND survey of public school educators, about one quarter of principals and one out of ten teachers report being harassed for teaching about race, racism, or bias.107 All together, 52 percent of teachers who reported living in states with educational gag orders say that these laws have affected what and how they teach. Black teachers and those teaching social science and English language arts are especially likely to say they have censored themselves.108

Principals and school superintendents are changing their behavior as well. In 2018, 59 percent said they offered their teachers professional development training on how to introduce students to the literature and history of people from different ethnic and racial backgrounds. In 2022, only 46 percent did—and the drop-off was even starker in politically conservative school districts.109 After Iowa passed a K–12 educational gag order in 2021, teachers at the Fairfield Community School District asked their superintendent whether they were permitted under the law to offer their opinions on topics like slavery. She replied, “To say ‘Is slavery wrong?’—I really need to delve into it to see is that part of what we can or cannot say.”110

As the incident above indicates, the impact of these laws cannot be conveyed in numbers and percentages. Real students are being affected, and the careers of real teachers are on the line. Quotes from teachers contacted for the recent studies paint a bleak picture of the choices available to educators in affected states.

- Middle school English teacher: “The past two years have made me nervous about teaching Frederick Douglass because I don’t think the people in my community know the difference between teaching [Black] history and teaching critical race theory.”111

- High school science teacher: “We work in an atmosphere of fear and paranoia to even teach the content contained in our standards.”112

- Middle school teacher in Virginia: “The governor has set up a tattle tale line [a “tip line” for violations of the state’s educational gag order that operated during 2022]. . . .For the first time this year I was like, should I even include parts of those lessons [about the Civil War and Reconstruction]? Which breaks my heart.”113

- Elementary school teacher in Tennessee: “We were told verbally during a PowerPoint presentation with the district counsel that we should avoid any controversial issues. . . . My colleagues are shying away from teaching anything in history or social studies that could be offensive.”114

- K–12 teacher in Tennessee: “As a social studies department we were told we cannot say things are racist [or that] it was sexist to keep women from voting.”115

- K–12 music teacher in Tennessee: “The law in Tennessee has caused me to rethink my use of certain African American spirituals to avoid discussions that might be misconstrued to violate the law.”116

- First-year K–12 music teacher: “[My state’s] Department of Justice website has an online form where someone can easily report a teacher for going against the [divisive concepts] bill. . . . I was scared to talk about jazz or the blues. . . . I cannot authentically teach the genre without talking about race, but I don’t want to get reported or get in trouble.”117

- K–12 music teacher: “During a general music class occurring the same day that [my state] passed its divisive concept law, I was discussing Benny Goodman[’s opposition to segregation]. . . . An hour later, I received an email from a parent. . . . ‘This is inappropriate, unprofessional, and illegal. You should be jailed, sued, and fired. This law is meant to stop students being subjected to this kind of information.’ . . . My assistant principal says, ‘. . . Just apologize to the parent to smooth things over so that this will go away.”118

In addition to widespread accounts of the broad chilling effect educational gag orders have created, news accounts have continued to document instances of teachers and districts being punished or their speech censored under the laws. The following are just a few examples from the past six months.

- A fifth-grade teacher in Georgia was fired because she read to her students My Shadow Is Purple, a storybook about identity and acceptance. According to the school board, she had violated the state’s prohibition against instruction on “divisive concepts.”119

- When a comic book researcher was invited to an Atlanta school to discuss Batman, he was told that he could not inform students that one of the character’s cocreators had a gay son. According to a school representative, disclosure of this fact might lead to discussions of sexuality without parental permission.120

- Citing the recent expansion of Florida HB 1557, the superintendent for Charlotte County, Florida, directed school librarians to remove all books featuring LGBTQ+ characters or themes from the elementary and middle school libraries. The superintendent also told teachers that they “need to be aware of what their students are reading for silent sustained reading in class, or book reports, or anything involving instruction, even if it is student-selected to ensure they are not violating this rule. . . . [LGBTQ+] characters and themes cannot exist.”121

All of this censorship is exacerbated by the vague and confusing way educational gag orders are written and the lack of guidance provided to school districts and teachers. For more than a year now, districts in Florida have begged the state’s Department of Education for guidance. “Just give us an answer, yes or no,” implored one Florida superintendent, “and we’ll know which way to go.”122 Can a teacher show a film or read a story with an openly gay character? What about classic works of literature, like the Bible, that describe sex, violence, and masturbation? These are not idle questions. In a trove of emails released via a public records request, the general counsels of Florida school districts are shown posing these exact hypotheticals to the Department of Education following passage of the state’s gag orders, only to be ignored.123 And on those rare occasions when the state does provide answers, it has done so in such a contradictory and muddled way that it creates more uncertainty instead of less.124

![]() The law in Tennessee has caused me to rethink my use of certain African American spirituals to avoid discussions that might be misconstrued to violate the law.

The law in Tennessee has caused me to rethink my use of certain African American spirituals to avoid discussions that might be misconstrued to violate the law.

Anonymous K-12 music teacher in Tennessee

A similar dynamic is now playing out in Iowa, where Governor Kim Reynolds and the state board of education have responded to requests for guidance for how school districts should enforce SF 496 by stating that they will begin providing such guidance on December 28. However, schools are required to be in compliance with the law by January 1, 2024—four days later.125

Even when K–12 gag orders are clearly written, officials often enforce them in a capricious and chaotic way. For example, in the spring of 2023, a veteran South Carolina teacher was punished because, according to two student complaints, she showed her class a pair of videos about racism in America that made the students feel uncomfortable.126 According to her school, this violates HB 4300, the state’s educational gag order. But the text of HB 4300 only prohibits teachers from telling students that they “should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his race or sex.”127 Nothing in the law blocks teachers from using some material just because it might have the effect of making a student feel discomfort—a key distinction that was entirely lost on school officials. PEN America has seen this same confusion play out in Oklahoma as well.128 Educators have accused lawmakers of trying to make it a crime to teach students about controversial topics; the record suggests that this is indeed how these laws are playing out on the ground.

All of this coincides with an exodus of teachers. According to the Florida Education Association, the state had nearly 7,000 vacant teaching positions at the start of the 2023–24 school year, a marked increase over previous years. The state government contests this claim, putting the number of vacancies at closer to 5,000.129 Either way, it is one of the worst in the country, even after accounting for Florida’s large size.130 And while this shortage has many causes, the state’s educational gag orders are undoubtedly part of the story. “I just talked to one [Florida] teacher yesterday who is leaving and she said, ‘I can’t teach like this,’” recounted Rebecca Pringle, head of the National Education Association. “‘I can’t teach while worrying that they’re coming after my license, or I’m committing a felony.’ They’re leaving in protest.”131

The experiences of these educators inevitably has an impact on the quality of education schools are able to offer their students. If teachers are afraid to make any mention of race or LGBTQ+ identities in the classroom, if they are afraid to answer student questions, if quality educators are leaving and cannot be replaced, students are the ones who suffer most.

Even when K–12 gag orders are clearly written, officials often enforce them in a capricious and chaotic way. For example, in the spring of 2023, a veteran South Carolina teacher was punished because, according to two student complaints, she showed her class a pair of videos about racism in America that made the students feel uncomfortable.

A fifth-grade teacher in Georgia was fired because she read to her students My Shadow Is Purple, a storybook about identity and acceptance. According to the school board, she had violated the state’s prohibition against instruction on “divisive concepts.”

Colleges and Universities

The situation among college and university faculty is no better. Here, again, the primary impact has been fear.

A January 2023 ProPublica article found this dynamic on vivid display during the four and a half months in which the Stop WOKE Act was in effect for higher ed institutions. For instance, in response to the law and the political climate, the University of Central Florida’s sociology department canceled every course that it offered on race. Florida Gulf Coast University renamed its Center for Critical Race and Ethnic Studies to eliminate the word critical, and at Florida State University, an instructor weeded out student-suggested questions about white privilege from class discussions. Another Florida State University professor, a sociologist who teaches and researches critical race theory, reported that her department chair urged her to defer her tenure application for a year.132

These issues are not limited to Florida, nor known to us only through anecdotes. The August 2023 AAUP survey of over 4,000 public university faculty in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas found that 32 percent are actively considering interviewing for employment elsewhere in the coming year.133 In Florida—the only one of the four states with a higher education gag order on the books—that number rises to 46 percent.134

The professors surveyed by the AAUP paint an alarming picture of academic freedom in public universities under censorship.135 The following comments from faculty at public colleges in Florida describe an environment of extreme fear, more reminiscent of an authoritarian state than a democratic university:

- “I constantly feel like I am one denunciation away from a derailed life and career.”

- “I’ve . . . received pressure from students to give them a grade that they want in exchange for not submitting a complaint about me.”

- “I live in fear of vindictive students and administrators who may not like my teaching and research.”

- “I have been told to revise my course syllabi to remove language that might cause trouble.”

- “We have to replace chapters that include the notion of ‘white privilege’ with our own [PowerPoints] that do not mention it.”

- “Because my work deals with investigation [sic] structural inequity, I can be disciplined or fired for even saying that it exists.”

- “I was hired to teach and research gender and DEI issues. The new FL legislation is paralyzing. I have no idea what I am supposed to do.”

- “I’m reluctant to teach classes with the term ‘race’ or ‘gender’ in the course name for fear of being targeted by the state. I’m also reluctant to address issues of race or gender in class for fear of being targeted by students. I’ve taken those elements out of my courses.”

- “Those of us in [general education] classes are removing any content that it is obvious we will be castigated for teaching. For instance when teaching development of humans we will not teach it period. Switching to cats or frogs. And we have all decided we are not safe teaching reproductive biology. If a student asks a question and we give an honest answer we will be fired bc of the new laws.”

- “I am a philosopher and it is my job to present as many arguments and counterarguments as I can and to teach my students how to evaluate these. I am fearful that positions that I defend in the line of duty—whether or not I actually hold them—can and will be used against me. How can I be a competent teacher in such a climate?”

- “A reviewer for a grant I recently submitted stated that the proposal would be stronger if I more directly addressed issues of racialized violence in my project. I do very directly address these issues in the work, but as that grant proposal is part of the public record and I am pre-tenure, I did not detail that aspect of the project. I find myself routinely self-censoring in this way.”

Comments from faculty at public colleges in Texas, which passed a DEI ban this legislative cycle, suggest that the chilling effect on professors is worsening there as well.

- “Language is being silenced. Not allowed to use the words diversity, equity, or inclusion. Voice is being silenced due to my perception—fear by institutional leaders of losing public funds due to threats of the legislation for not completely banning every aspect of DEI.”

- “I avoid bringing things up in faculty meeting [sic]. I am dubious about external funding—it is likely that colleagues/peer reviewers in other states will be hesitant to award funding to an instutition [sic] that by definition cannot explicitly support the efforts necessary to increase the scientific workforce.”

- “Students, especially undergrads, who were supported by diversity programing [sic]/initiatives feel more vulnerable on campus and this is reflected in the classroom.”

- “We are being forced to change the name of one of our courses [on cultural awareness]. . . . This could put our accreditation at risk.”

- “DEI is a requirement of accreditation for the professional graduate degree program in which I teach. However, our university is requiring that we remove any DEI language from our website and reframe any committees or initiatives focused on these issues.”

These comments portray a profession riven by government censorship, institutional censorship, and self-censorship as a result of these laws. Faculty departures and transfers, unfilled vacancies, weak applicant pools for graduate students, and lost grants and research collaborations are among the many costs of these laws. It is little wonder, therefore, that 85 percent of Florida faculty and about two-thirds of Texas faculty surveyed would not recommend their state to a prospective graduate student or faculty colleague.136

These issues are not limited to Florida, nor known to us only through anecdotes. The August 2023 AAUP survey of over 4,000 public university faculty in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas found that 32 percent are actively considering interviewing for employment elsewhere in the coming year. ![]() I was hired to teach and research gender and DEI issues. The new FL legislation is paralyzing. I have no idea what I am supposed to do.

I was hired to teach and research gender and DEI issues. The new FL legislation is paralyzing. I have no idea what I am supposed to do.

Anonymous Florida professor

Students and supporters protest ahead of a board of trustees meeting at New College of Florida in February 2023. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

The AAUP survey is the most comprehensive study to date that shows the damaging effect of educational gag orders and governance restrictions on higher education, but others who have studied the issue describe a similar picture. According to media reports, dozens of faculty have fled New College of Florida since its takeover by an ideologically motivated board of trustees.137 And in Iowa, poorly drafted laws and vague terminology have cast a pall over the classroom.138 It is too soon to say how California’s new DEIA regulations will affect faculty at the state’s community colleges (the regulations were formally adopted in May 2023), but the impact is likely to be similar. The plaintiffs in the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression lawsuit challenging these regulations already say that they have felt forced to rewrite their syllabi and remove from their lectures certain conversations about race.139

Even students are starting to feel the impact. According to a survey of Florida high schoolers, one in eight say they refuse to attend a Florida public college or university because of the DeSantis administration’s education policies.140